We continue our series on Racism in America with four short articles this time. I hope you had a chance to dig into Bishop Mark Sykes’ courageous pastoral on racism and white supremacy that I published in Tuesday. If not, you can find it on the right side of my site at the top of the archive column.

The first one today is from Archbishop Wilton Gregory, of the Archdiocese of Washington, D.C.,who is black. The middle two are the New York Times 1619 Project, a large research project on slavery and its effects on America life and our economy since its the first slave ship came to our shores. And the last one is from the Sierra Club about how the Trump administration has made our air pollution worse especially on our black communities.

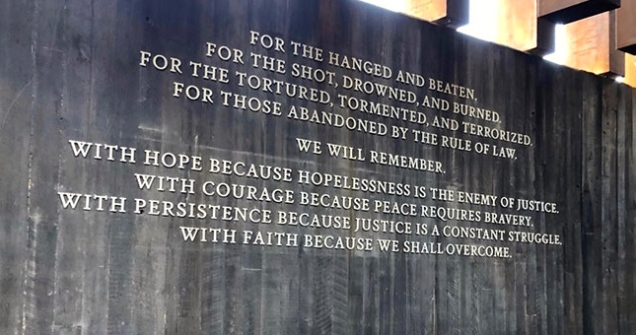

(The images on this page are taken from the Peace and Justice Memorial in Montgomery, Alabama to commemorate the lives of lynched and murdered black folk.) Hundreds of there names are memorialized on huge upside down bronze blocks and some of their ashes are there as well.

First, we hear from Archbishop Wilton Gregory . . . .

Our nation is in pain and in crisis, with angry, peaceful protesters demanding justice; with some lawless attacks on places and people; and with leaders who are failing us. At the same time, a deadly COVID-19 pandemic that touches all of us has exposed pervasive injustices which leave people and communities of color far more likely to suffer and die, lose work and wages, and risk their health and lives in essential jobs.

For Catholics and all believers, racism is more than a moral and national failure; it is a sin and a test of faith. Racism is America’s original sin, enduring legacy, and current crisis. Racist attitudes and actions, along with white supremacy and privilege, destroy the lives and diminish the dignity of African-Americans and so many other Americans. Racism also threatens the humanity of all of us and the common good. Racism divides us, reveals our lack of moral integrity, limits our capacity to act together, denies the talents and contributions of so many, and convicts us of violating the religious principles and the national values we proclaim.

~ Archbishop Wilton Gregory ~ Racism in our Streets and Structures.

The next two articles are from the New York Times 1692 Project.

The 1619 Project is an ongoing initiative from The New York Times Magazine that began in August 2019, the 400th anniversary of the beginning of history by placing the consequences of slavery and the contributions of black Americans at the very center of our national narrative.

A story of one black soldier coming back from war . . .

The day of days for America and her allies. Crowds before the White House await the announcement.

I have received this afternoon a message from the Japanese government which specifies the unconditional surrender of Japan.

Reporters rush out to relay the news to an anxious world and touch off celebrations throughout the country. Joy is unconfined.

It’s February of 1946, and a young black man is sitting on a bus watching the Georgia pines fly past the windows. He’s on his way to see his wife, and he’s probably very excited, because he’s been away at war, and he hasn’t seen her in a very long time. He’d been fighting for this country in World War II, and just that day, he’d been honorably discharged for his service. But he is a black man who is returning to the Jim Crow South.

“You can never whip these birds if you don’t keep you and them separate..

“But to tell me that I don’t even have the right to fight to protect the white race —

“We are going to maintain segregated schools down in Dixie.

“Well, I think their aim is mixed marriages and becoming equal with the whites.

“You’ve got to keep your white and the black separate.”

What happened on that day is a story that will be told across the country.

Good morning. This is Orson Welles speaking. I’d like to read to you an affidavit.

It was a story that would actually change the course of history.

I, Isaac Woodard Jr., being duly sworn to depose and state as follows, that I am 27 years old and a veteran of the United States Army, having served 15 months in the South Pacific and earned one battle star. I was honorably discharged on February 12, 1942.

He’s riding the bus through Georgia.

At one hour out of Atlanta, the bus driver stopped at a small drugstore.

He wants to get off and use the restroom.

He stopped. I asked him if he had time to wait for me until I had a chance to go the restroom. He cursed and said no. When he cursed me, I cursed him back. When the bus got to —

The bus driver gets upset with him. They have a little bit of an argument. Woodard doesn’t think much of it. He goes to the bathroom, runs back to the bus, and the bus keeps going. But then, a few miles down the road, the bus stops, and the bus driver gets off the bus, and then calls and tells Woodard that he needs to get off the bus as well. So Woodard gets off the bus, and before he can even utter a word —

When the bus got to Aiken, he got off and went and got the police. They didn’t give me a chance to explain. The policeman struck me with a billy across my head and told me to shut up.

He’s struck in the head by a police officer.

— by my left arm and twisted it behind my back. I figured he was trying to make me resist. I did not resist against him. He asked me, was I discharged, and I told him yes. When I said yes, that is when he started beating me with a billy, hitting me across the top of the head. After that, I grabbed his billy and wrung it out of his hand. Another policeman came up and threw his gun on me and told me to drop the billy or he’d drop me, so I dropped the billy. After I dropped the billy, the second policeman held his gun on me while the other one was beating me.

And the blows keep coming, and they keep coming, to the point that Woodard loses consciousness.

Woodard is still wearing his crisp Army uniform. He’s been discharged just a few hours earlier. When he comes to, he’s in a jail.

I woke up next morning and could not see.

So Woodard’s beating was not at all unusual. World War II had done exactly what many white people had feared, that once black people were allowed to fight in the military, and when they traveled abroad and they experienced what it was like not to live under a system of racial apartheid, that it would be much harder to control them when they came back. Black men in their uniforms were seen as being unduly proud.

So these men who had served their country, who had come home proudly wearing the uniform to show their service for their country, would find that this actually made them a target of some of the most severe violence.

But what was unusual was what happened after. Woodard’s case was picked up by the N.A.A.C.P., and they take him on a bit of a tour. They take photographs of him. Those photographs are sent out to newspapers and to fundraising efforts, where they’re saying, look what happened to this man who served his country. It’s that spark that finally determines among millions of black people that enough is enough.

And that’s largely seen as one of the sparks of the modern civil rights movement.

We have people coming in from all over the country. I suspect that we will have — (garbled and unfinished sentence.)

The second sustained movement of black people trying to secure equal rights before the law and an equal place in this democracy.

During the early weeks of February 1960, the demonstrations that came to be called the sit-in movement exploded across the South.

Negro youngsters paraded with placards, handed out literature, and tried to sit in at lunch counters.

I think, honestly, many of us didn’t realize just how important our movement would grow to be.

Official reaction was both swift and severe.

Don’t blame a cracker in Georgia for your injustices. The government is responsible for the injustices. The government can bring these injustices to halt.

How long? Not long. Because the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice. Glory! Hallelujah! Glory! Hallelujah!

And in 1968, 350 years after the introduction of the first enslaved Africans into the colonies.

This Civil Rights Act is a challenge to all of us.

— Congress passes the last of the great civil rights legislation.

— to go work in our communities and our states, in our homes and in our hearts —

It ends legal discrimination on the basis of race from all aspects of American life.

— to eliminate the last vestiges of injustice in our beloved country.

We often think of the civil rights movement as being about black rights, but the civil rights movement was never just about the rights of black people. It was about making the ideals of the Constitution whole. And so when you look at the laws born out of black resistance, these laws are guaranteeing rights for all Americans.

This experience, which black Americans were having, did not go unnoticed by the rest of America.

I mean, basically every other rights struggle that we have seen . . .

Now we fought the public accommodations fight 10 years ago with the blacks. Are we going to have to start all over again with women?

Disability rights, gay rights, women’s rights —

That people with disabilities were still victims of segregation and discrimination.

— all come from the efforts of the black civil rights struggles.

Equal rights. Equals rights to have a job, to have respect, to not be viewed as a piece of meat.

No Americans will ever again be deprived of their basic guarantee of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

Celebrations erupted on the steps of the Supreme Court.

One of its most momentous civil rights decisions. The Supreme Court found gay and lesbian Americans have a constitutional right to marry. The majority found its justification in the 14th Amendment, written after the Civil War to extend equal protection under law to freed slaves.

So we are raised to think about 1776 as the beginning of our democracy, but when that ship arrives on the horizon at Point Comfort in 1619, that decision made by the colonists to purchase that group of 20 to 30 human beings, that was a beginning too. And it would actually be those very people who were denied citizenship in their own country, who were denied the protections of our founding documents, who would fight the hardest and most successfully to make those ideals real, not just for themselves but for all Americans. It is black people who have been the perfectors of this democracy.

When I was a kid — it must have been in fifth or sixth grade. Our teacher gave us an assignment. It was a social studies class, and we were learning about different places that people came from, and this was her way of kind of telling the story of the great American melting pot. So she told us all to research our ancestral land and to write a small report about it, and then to draw a flag. I remember kind of looking up and making eye contact with the other black girl who was in the class, because we didn’t really have an ancestral land that we knew of. Slavery had made it so that we didn’t know where we came from in Africa. We didn’t have a specific country. And we could say that we were from the whole continent, but even so, there’s no such thing as an African flag. And so I remember going to the globe by my teacher’s desk — it was on the windowpane along the left side of the classroom — and spinning it to the continent of Africa and just picking a random African country.

So I went back to my desk, and I drew that random African country’s flag, and I wrote a report about it. And I felt ashamed. I felt ashamed, one, because I was lying, but I also felt ashamed because I felt like I should have some other country, and that all the other kids could trace their roots elsewhere, and I could only trace my roots to the country that had enslaved us.

I wish now that I could go back and talk to my younger self and tell her that she should not be ashamed, that this is her ancestral home, that she should be as proud to be an American as her dad was, and that she should boldly and proudly draw those stars and stripes and claim this country as her own.

0 ~ Unattributed

Nothing is more racist than religion. God is a supremacist baby killer and woman hater.

Whereas I certainly do NOT AGREE with my commenter’s remarks; Hw posted this on his site: “At the heart of the First Amendment is the recognition of the fundamental importance of the free flow of ideas and opinions on matters of public interest and concern. The freedom to speak one’s mind is not only an aspect of individual liberty, and thus a good in itself, but also is essential to the common quest for truth and the vitality of society as a whole.” (Chief Justice Renquist) Therefore, I am posting his comment, rather than deleting it.